Following the Songlines

Thirty-five years of Songs, Stories, and Wanderings in the World.

To Grace

“’Twas grace that taught my heart to fear and grace my fears relived.”

***

Life is an open book.

Write the script that leads to love.

(Author, The Old Dairy, Earlston. 2000)

***

Latitude Sunset

Sun sets, between hills of the moor.

Shadows stretch along West Road,

A scree fall turns in silhouette beyond Whin Sill,

Colours dilute through Hadrian’s Wall.

Lakes deepen dark, past Derwent,

Stretching debatable land to nuclear sea.

Ulster sands dampen, lights`last salt sting,

and to sleep liquid night quenches our falling flaming songs.

In the mountains beyond, silence…

(Whickham, Newcastle Upon Tyne 1980s)

Cover Photo: “F# Magpie” by Marc Perry

Copyright © 2025 Marc Perry. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including digitally, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations used in reviews, articles, or other non-commercial uses permitted by copyright law.

For permission requests, please contact: perryeyes@gmail.com

“Following the Songlines” chronicles thirty-five years of songs, stories, and wanderings across the world, weaving together journalism, memoir, music, poetry, and field notes.

Click links to navigate to content.

Contents:

Introduction: From the Mountains Beyond Silence

The United States of America. Following the Songlines (1990/1)

Israel and Egypt. Eyes Wide Open To The World (1993)

Ireland. A Little Lyrical Light (1993)

England And Scotland. Islands, Castles and Gardens (1994-2011)

Greece. Debt Heartache and Joy (2011)

United Kingdom. Balls of Steel (2011)

Afghanistan. Searching for Lion; Freedom At 4 AM (2013)

France. Pitched Up in Paris (2013)

Turkey. In Limbo, in Istanbul (2013)

Serbia. Angelic Stairway (2013)

Bulgaria. A Dead End to Dobrinovo (2016)

Kosovo. Travels Between Faiths (2013-16)

Bosnia. First World War Centenary (2014)

North Macedonia & Serbia. Following in Refugee Footsteps (2015/16)

Belgium. The Sun Has Finally Sunk (Brexit 2016)

Northumberland. In The Army Now / Seeking The Shepherd (2017)

Ireland. Winifreda’s Return (2018)

The United States of America. Open My Heart at Wounded Knee (2024)

Marc Perry

Marc Perry is a writer, photographer, and wanderer whose work spans continents, cultures, and conflicts. Born in the post-industrial North East of England, he has spent over three decades following a restless urge to experience the world up close and personal — from the jazz-infused streets of New Orleans to the biblical landscapes of Israel and Egypt, from Afghan mountains to sacred monasteries and remote Northumbrian farms.

His writing explores conflict and reconciliation, faith and forgiveness, and the quiet resilience that emerges in unexpected places, often carried on the notes of a song. Over the years, he has worked as a journalist, teacher, media officer, reservist soldier, and editor-in-chief for interfaith initiatives.

Marc’s first book, Freedom at 4 AM, emerged during his time as a media officer in Kabul. He later published Kosovo Uncovered and Kosovo Declassified: War In Their Words, both explorations of Kosovo’s complex history and people. Following the Songlines is his most personal work to date — a testament to the transformative power of wandering, listening, and sharing stories that bind us together.

He currently runs The Transatlantic Times on Substack, exploring the rich cultural, musical and historical ties between Europe and North America.

“Solvitus Ambulando”

(It is solved by walking)

Introduction: From the Mountains Beyond Silence

Our paths are plural, but our destination is singular. For me, wandering and writing are one, be it trotting the globe or across the village green. Biographies of travel writers and historians that influenced the writings within these pages – such as Bruce Chatwin, Patrick Leigh Fermor, Eric Newby, Rory Stewart and William Dalrymple – often begin with a long list of accomplishments, elite educational establishments and appointments within seemingly privileged worlds. The journalists who inspired me – Jan Morris, Fergal Keane, Kate Adie, John Simpson, Brian Hanrahan and Marie Colvin – often seem to be from a different stratum of baby-boomer ‘lucky breaks’ too. Though their first steps do not resemble mine, their desire to explore beyond the shoreline of the place of their birth does. Their writings, flourishing from the same sense of investigation and wanderlust, signpost a long lineage of writers whose tenacity and intellect I both wholeheartedly embrace and applaud.

Other wanderers, writers and musicians, however, permitted me to dream that a migratory life of writing was possible: Laurie Lee, Bob Dylan, Jack Kerouac, Jack London, Woody Guthrie and the bluesmen of the Mississippi. Invariably, they were American, unfettered by the class system, free to ramble and a-roam, and somehow able to push through and publish to a mass audience without having to pass through English establishment gatekeepers. So, it was inevitable that my dreams would coalesce around departing the then economically depressed North East of England for the United States of America. I secretly concealed copies of travel guides with ‘on a shoestring’ titles in a bedside box next to the pillow where I would literally lay down my weary, head. Song lyrics would become my solace.

“When evening falls so hard around your feet; lay down your weary tune, lay down; walk that ribbon of highway.”

Mirroring the external landscape of desolate deindustrialisation in 80s Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, an internal depression of my own surfaced. Early school struggles with my vision and a consequent inability to track words on a page evenly, see the board, sequence letters or spell correctly set in motion a long series of poor course choices, leading to a frustrating sense of failure that would become the driving force to escape. On a spiritual level, it was all something of my fate from birth, a gift, to push through the darkness on the edge of town towards some sort of self-actualisation.

The university of life always outwits academia, but my first taste of university would open doors that had nothing to do with my course or talents. I would spend long hours in the arts library discovering images, words and music that had nothing in common with the subjects I was there to study. When my final exam essay posed the question: “What has science taught you?” I answered: “The extent of my ignorance.” But science opened the door to a student visa stamp in my passport, to two summers in the USA, to a grasp of freedom. And so, eventually, one summer morning I arose and walked off to look for America, following the songlines of popular music, greyhounding across the USA, then out into the world.

Like other Northerners before me, my rebellious desires would shout, We get out of this place, but this inclination would continue to conflict with the unwritten rules of societal expectation – to let it all go, and get a job with a pension. Work would therefore mutate from a means to pay for travel, to a means to travel in itself: from nurse, butler, gardener and farmer, to journalist, reservist soldier, editor and writer. Wandering would become a way of life, even though I love coming in from the garden to write.

All of the stories within this book begin with songs or poems; indeed, the phrase From the Mountains Beyond Silence, is taken from a short poem, Latitude Sunset, penned in late teenage years that’s soaked in the yearning to move, to see what’s around the bend and beyond the horizon. This book is therefore the consequence of a series of creative outpourings that set my feet in motion: hence the inclusion of many of the ditties that propelled my journey forward.

There’s a certain prescience in songs, poems and sonnets. Through all artistic expression we expose our conscious and subconscious memories, dreams, fantasies, influences, and orientations – be they past, present or future. On close reading, some readers might observe how certain verses contain gems of prescience, foreshadowing future sojourns with themes of war, exile, forgiveness and redemption. During the journey, I attended ‘school of life’ classes in resolving inner conflict; following ‘the path’ when it presents; and striving to express creativity, without dying of starvation.

The reason some are called to write and shoot photographs is to record the present, knowing it will become the past. Recording the present is the act of journalism, and journalism is the first draft of history. A wise historian, therefore, records the present, knowing it will become the past. The stories here span thirty-five years, but only cover a handful of the countries where I spent longer periods. They can be read individually or as part of a continuum. They start when I’m twenty years old and close as I reach the age of fifty-five, so I hope you, as the reader, witness changes in maturity, voice, style, and subject. The first stories, including those from America, Israel and Egypt, are largely reconstructed from notebooks and have been softly adjusted with small revisions. From 2012 onwards, the pieces are reproduced as they emerged, fully fledged.

Travellers will tell other travellers the deepest secrets of their hearts. I’ve resisted describing every detail of my personal life in this book, for reasons of privacy, confidentiality and integrity. Many significant people behind the words on these pages are never mentioned, nor would they wish to be, but for richer and poorer, I thank every one of them.

Some of us are born into this world with a sense of gravitas. Others, such as myself, fall as droplets of dew, seeking an ocean of wholeness ultimately found beyond these earthly horizons. Within the pages of this book, you’ll find some of my stories, sojourns, and songlines walking, like the song Life’s Railway to Heaven, towards “that distant shore, where the angels wait to join us, in God’s grace forever more.”

Polite warning: If you can’t stomach swearing, some of these stories may ruffle your feathers. Reflecting the reality of how some people speak, I’ve included language that is sometimes livelier than you may want, but stops short of the full-fat version. This is especially true for stories including soldiers and others near the front lines, who’d have little to say if they didn’t swear. I’ve also chosen to include spellings that accentuate accents, so a little voice acting will help bring the stories to life.

“No talking to imaginary people.”

Notice above telephone in Hummingbird Grill, New Orleans.

***

Jazz cat asleep,

In New Orleans Record box.

Mississippi purring.

(Preservation Hall, New Orleans 1991)

***

“No one ever went bust underestimating the American public.”

Mike - Man on Amtrak. (Was once a roadie to Joan Baez)

(Chicago-New York Train. 1991)

***

“You can’t stop the birds of misery from flying over your head. But you can prevent them from building nests in your hair.”

(Bar sign, New Providence Island, Bahamas)

The United States of America

Following the Songlines (1990/91)

A songline is a pathway across the land, often through song, story, and dance. These pathways are repositories of cultural knowledge, including navigation, history, and social structures. Songlines are crucial for transmitting knowledge across generations.

The yearning restlessness of many millions starts with a step towards reinvention and ends with America. This book begins and ends in the USA. Since my first visit there as a twenty-year-old, the country has continuously captivated me with its culture, landscapes, extroversion and inventiveness. It’s the America of Poe and Parker, Kerouac and Coltrane, Hopper and Hemingway, Waits and Waters or Domino and Dylan, rather than the one of Disneyland, Vegas or Beverley Hills that fascinates me. The ‘real’ America: of warm welcomes, radio, railways and wide-open spaces…

What staggers me about the American landscape, beyond its beauty and scale, is our ability to read it, no matter where we come from. It all seems, somehow, familiar. Canyons, railroad crossings, grasslands, red Dutch barns, telegraph poles, reservations, mountain ranges materialising from plains and dust billowing trucks motoring long straight roads receding into distant horizons. All of it familiar, through the extraordinary soft power of American cultural influence. On a personal level, the epicentre of that cultural influence is song, but it could also include literature, cinema, art, photography, and that most commercial of American activities, advertising. My motto back then was “Dream it - Do it.” (Just like the Nike slogan!)

I was reading Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and dreaming of hitting the highway myself. My bedroom walls were plastered with posters of the New York skyline and a shining golden saxophone. John Clellon Holmes’s novel “The Horn” accompanied late-night listening to Bird, Dizzy, Coltrane and Miles. My book shelves bulged with American authors including The Beats: (Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Lawrence Ferlinghetti); and wanderers such as Jack London, Charles Bukowski, and literary writers such as Thomas Wolfe, Walt Whitman, Paul Auster, Maya Angelou and Harper Lee; the list goes on, and on, and on. I was subconsciously creating a road map of songlines cutting across the American continent.

Like many of us, the landscape of my imagination was filled with the USA long before travelling there. Most vividly beginning with images buried within the songs of Bruce Springsteen, Bob Dylan, and Tom Waits, before digging deeper to unearth gold in their influences, in the sounds of Folk, Jazz, Blues, Country, Rock’ n’ Roll and Rock. The list of influences is inexhaustible but could include: Woody Guthrie, Muddy Waters, Lightning Hopkins, Chuck Berry, Hank Williams, JJ Cale, Little Feat and The Band. All of this musicology was brought home through the “Where the Delta meets the Tyne” creations of Mark Knopfler, the Celtic soul of Van Morrison and the category-defying Sting. From this enormous reservoir of song, wide-screen shots of striking cinematic potency were burned into my imagination.

Taken as a whole, the American songbook might inspire the urge to get your kicks on Route 66, take everything down to Highway 61, make your way to Sweet Home Alabama, sleep in the desert tonight, roam a thousand miles of track or call long-distance information from Memphis, Tennessee. Throughout the sojourn ahead, you will find many references to songs italicised. The lyrics in those songs provide anchors, reference points in landscapes, song-lines that stir the soul to the extent that you may even wish to see the same places for yourself. The railroads Woody Guthrie rode, the roads Springsteen ran down, the road-weary downs Hank Williams lamented, are just some of the wellsprings of songlines that overlay this journey. It’s a geography often older than the lyrics themselves, yet indelibly marked by the streams of songwriters who have passed through, soaked it up and sung it out.

Long before the blue-pink aurora of sunrise, when nothing passes your car window but fleeting starlight shadows the songlines reveal themselves in stark physical form. Across the length and breadth of America, square mile after square mile, the red flashing lights of radio network towers blink unceasingly, beaming sound waves first recorded on wax, then acetate, vinyl, tape and digital across a continent and out to the world. It's truly an extraordinary business that brought, and still brings, music to our ears. Without the means of American success – the melting pot of immigrants and influences, the inventiveness, the mass markets and the wide-open space for expansion – we might never have heard a single song about the message of love the bluebird brings, Basin Street Blues, or Big Fun on the Bayou.

So, let’s rewind the tape. There I was one day, just a normal kid, then there I was the next, dreaming it and doing it on my first big break from Britain, walking the streets in the land of the brave and free, notebook in one hand and a cassette recorder in the other. I was following the songlines straight up the Mississippi River, from the birthplace of Jazz to Sweet Home Chicago.

New Orleans

A Policeman behind me started singing in a sweet alto voice as I arrived in New Orleans by bus.

Is there any other way to arrive in the city that gave birth to jazz?

A torrential tropical storm blew through, kids were playing over a canal, people were running this way and that, covering their heads. Eventually, I found the hummingbird hotel, the downest, beatest flophouse a Kerouac kid could wish for, with a twenty-four-hour grease grill downstairs and a sign above the telephone reading: “No talking to imaginary friends.” At any moment, Tom Waits could have walked in, pushed up his cap and ordered hash browns over easy, chilli in a bowl. Neon flickered outside my bedroom window, floorboards were missing in the hallway, and I was living the ‘dream’. As I crossed the gaps in the floor to the shared bathroom, a clown emerged from the opposite room. Surely, I was still sleeping?

I followed the call, searching for A Moon Over Bourbon Street, and found a young man in a wheelchair playing a plastic saxophone, who told me the best place to go was Preservation Hall. At the hall entrance, I passed a cat sleeping in a box of records — a jazz cat, I supposed — purring, waiting, to join the second set of Dejan’s Olympian Brass Band on double bass. There was I, in the land promised by the scratchy sound of Satchmo’s trumpet on old 78s, a pilgrim paying homage to the Jazz saints who duly responded by marching in with that raggy ragtime bag of banjo, brass, bass drum, searing clarinet and stride piano. I couldn’t shift my eyes from the elderly piano player. When she shuffled over to the piano and sat down, the music flew through her fingers, transforming her into a strident twenty-year-old.

The next morning, I got up late and went down to the mighty Mississippi, where Entourage, a Zydeco band, mixed their accordion shuffle with the whistle-organ of a paddle steamer. Lying on the bankside in a hundred-degree heat, I wondered if Huckleberry Finn might float on by. The sax player collected money in his horn, persuading people to part with their dollars by playing sweet refrains and honking thank-yous. Somehow, the music angels arranged for me to see Fats Domino, Dr. John and the Neville Brothers live in their hometown. Some Americans took the young Englishman with a backpack under their wings and bought me a meal. It was all too much, so much so that the barmaid in a great corridor bar cried when we left... and I will never know why.

Memphis to Chicago

John Hiatt’s Memphis in the Meantime pulsated in my headphones as the train sped along, straight outta the Mississippi delta and across the Pontchartrain. My nose was bent to the window like an excited four-year-old kid. The Mississippi Delta might have been shining like a national guitar, but I was heading for Sun Studios rather than Graceland. Memphis was quieter back then. A blues combo was chugging out a groove on the street, and a guy dancing with his wife started to ask me questions…

Where did I come from? (England)

How come I spoke such good English? (!?)

Did I want to dance with his wife? (No thanks, not heard that one before)

Was I a racist? (gulp)

I was Walking in Memphis, down a wide road that seemed as anonymous as any other street, except for its passage to Sam Phillips’ Sun Studios. Entering by the front door and crossing to the small studio, I imagined Elvis and Jerry Lee Lewis doing the same, shaking hands with Sam and smashing out Jailhouse Rock and Great Balls of Fire onto acetates that would spin the world off its axis. One bass, one drummer, one Piano, a Guitar and a voice, that’s all it took to Shake Rattle and Roll the planet. Later in the day, I met two guys living out their rock and roll dreams, playing Buddy Holly and Eddy Cochran songs in a Memphis Café. Their guitar chord shapes were still a mystery to me, an unfathomable piece of magic performed by otherworldly immortals.

Sweet Home Chicago

Chicago Union Station was a cathedral of light and sound, the concourse of millions of lives heading North, East, South and West to seek work, fame or fortune. Here I was, pacing a path in the same station Louis Armstrong had arrived in when he headed north. But my mission was simpler: to find the blues on Maxwell Street. I knew the street had been a long-time draw for the old bluesmen back in the day, but I underestimated how dilapidated the South Side of Chicago had become. The empty lots, abandoned cars, and buckled trash cans should have given me and my travel companions a clue, but we bundled on. I hoped to find an old bluesman to talk to, but the street was quiet, except for a few stalls and a shop selling cassettes. “What you boys doing round here?” someone asked, making us jittery enough to forget the blues and just get going.

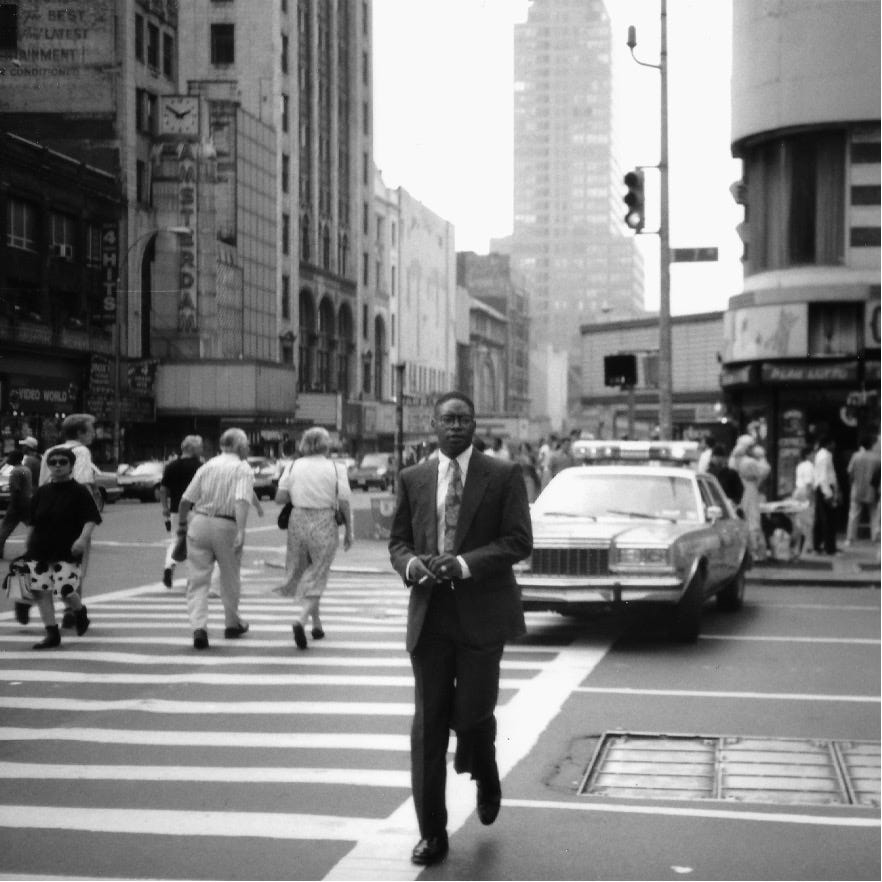

New York

Steam, lights, cabs, Puerto Ricans, jive talkers, cops, fire hydrants and ghetto blasters. My first impression was straight from the movies. The first stop was bohemian Greenwich Village, in the sticky night, drinking Cokes on the way. The songlines started weaving their magic instantly; I found a bar with Cheers on the telly — where everybody knows your name — and Eric Clapton singing She Don’t Lie, She Don’t Lie, She Don’t Lie... from the jukebox. While walking up Fifth Avenue, there was a saxophone blowing. I asked for Loverman. When he saw me searching for money in my pocket, he looked me straight in the eyes, leaned back, squeezed his eyes shut and blew a long flurry of notes. As we walked on, I could still hear him playing blocks away, way up 42nd Street, past Times Square, souvenirs, strip joints and all.

I took an early morning stroll. Guys were pushing trolleys and dragging crates past people living in cardboard boxes. I stopped for breakfast in an American diner: crepes, maple syrup and as much coffee as I could drink. A big emergency unfolded before my eyes, with hundreds of cops and the fire service in attendance. Two people had fallen down a hole in the street. TV crews were complaining about censorship.

I hired a bike and rode up and down 52nd and 53rd searching for anything from the old jazz scene. Nothing turned up, but I found the graffiti art that covered Dylan’s Oh Mercy album. Then it was on to Central Park. The first musicians I encountered were a trumpet player and someone on an electronic steel drum. There wasn’t much but sunbathing going on, so I rode down Fifth Avenue, where I found the same sax player from the previous night. It turned out he was a polite fella… called Michael Elliot, from Brooklyn: “They know me, people know me play tenor, the big silver. (He showed me the scar on his finger from the thumb rest.) The feelings of jazz, the alchemy and the feelings of jazz—playing jazz music is very high. If you want to be good, you’ve got to respect what you hear, and ah, I get caught up with it, you keep trying different techniques.”

Then it was down to Greenwich Village by daylight — full of students, Jewish ‘wise old men,’ people carrying guitars and people asking, “Do you need pot, man?” I found something from the old jazz scene in the tiny porch of the Village Vanguard on the corner of 7th and Perry. St. Mark’s looked dodgy, there were lots of peddlers, so I moved on to Washington Square, where I saw a stand off between some African musicians and a couple of others who wanted to jam with them: “Let’s go play with homeboy over there. I’m with you, man,” they concluded, walking away. I got lost, but I found a copy of the Village Voice to flick through, daydreaming of New York City loft spaces in a diner with toast, iced tea, salad, deep-fried chicken and French fries with ketchup. $6.80.

I headed down to the Lower East Side and got lost trying to find the Brooklyn Bridge. Down by the riverside, I smelled the sea air and fish markets as I rode along underneath an elevated road with thousands of limousines parked up underneath, their chauffeurs polishing away in the grime. [Years later, I would return and see the place utterly transformed.] The Brooklyn Bridge hovered over the Hudson with its massive, stately curve, six lanes of traffic, and echoes of Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. From Battery Park, I spotted the Statue of Liberty in silhouette, across the rough brown waters. Trying to find Broadway, I got lost again, but getting lost was the best way to find a city, and I was sure Chet Baker would have approved. I rode on through the dark financial district, past the stock exchange, finding Wall Street smaller than I expected for the size of its punch. The clock was against me. I had to return to 47th and 9th in half an hour. I found Broadway and cycled up it the wrong way; the danger was exhilarating, travelling against the flow of traffic. I got back late, but the bike shop dudes were busy selling a bike to an Italian couple and kid; the mother wisecracked about the price, “We’re going to be on diets for the next two weeks.”

Back at the YMCA, I was shocked to find I only had twenty dollars left. But there was still time to squeeze the last drop out of NYC, so I took the elevator up to the top of the Empire State. (How many other people had cracked a joke about life’s ups and downs with the lift operator?) It was a late August night with a clear view, and for the first time, I could understand where everything was — even planes landing at JFK. Back down on the street, I kept looking for my man and walked straight past him, oblivious, until I heard the scream of a clarinet. I turned. He was cool, relaxed and open, playing Take the A Train into my cassette recorder. Knackered and ready to sleep — Zzzzzz — I still found the energy to sneak up on the roof of the YMCA to soak it all in.

In the morning, I went for breakfast near the Port Authority: orange juice, coffee, a muffin with egg and ham, $1.90. Delicious. While eating, I overheard a conversation:

How y’ doin’?

Hey man, y’ know am goin’ crazy; they won’t know for three weeks if they’ll have to amputate it; the kid’s seventeen for Christ’s sake.

I was still moving, moving, moving — to the Metropolitan, to see Van Gogh, Turner, Picasso, Warhol and all those artists. I grabbed the rush-hour subway to JFK and got holed up when the lights went out. Sleeping through the flight to Glasgow, half-starved, I politely begged spare meals from the people around me. I was an introvert turned inside-out extrovert, by America.

Teaching Geordie to a Bedouin!

He bites into a fresh picked pepper,

“Peppa” he says...before climbing onto his “Tracta.”

(Kibutz Yahel, Israel, 1993)

***

“Aberystwyth, a nostalgic yearning which in of itself is more enjoyable than the place itself.”

***

For dyslexic agnostics- “Is there really a dog?”

“Pacifists unite” (if you let us).

(Al-Arab Hostel Philosophers, Jerusalem, 1993)

***

Arabian Drum

Metallic one.

Your curves seem a mystery to those,

Who has not been, from Mecca to Medina,

From mosque to golden mosque,

Send Allah's morning waking cry,

Let rip smack free your com-p-lex why,

Through stone splitting sun cast your laser high,

Glide your prayers on reflections of red coral, fly!

Let felucca sailors cast their sails,

Guide them in boats,

Upon the waves.

(The Cabin, Overdene, Northumberland, 2000)

Israel

Eyes Wide Open to the World (1993)

It wasn’t the songlines, but a teacher who signposted the way to the biblical rather than musical promised land. My Religious Education reports from school always came out glowing. One of my teachers, the Reverend Ross, was a priest. Under him, I wrote two extensive reports on the Middle East: one on Lebanon and one on Israel. The latter report directly led to my journey to Israel some seven or eight years later and, much later, into journalism. During my journey through the holy land, the scales fell from my eyes. Arriving at the close of 1993, the only mediated image of a Palestinian I’d ever heard up until then was accompanied by the word 'terrorist.' At the same time, full confrontation with the events of the Holocaust left me highly sensitised to Jewish history, genocide, and man’s potential for inhumanity to man. A dawning realisation of the consequences of the British Empire’s divide and rule legacy emerged too, providing fuel for critical inquiry into how nations deal with their past. If genocide and history weren’t enough, the trip stimulated a lifelong interest in conflict resolution.

Nothing could ever be the same after Israel. The trip wholly altered my perspective on life and simultaneously inspired my first piece of report writing. At 23 years of age, I had little sense of the timescale by which to measure the potential for implacability in human conflict. Some disagreements resolve quickly, while others have complexities that make reporting on them a human impossibility. The search for truth is both a journalistic and spiritual quest, and the bigger story is always driven by creative and destructive forces much deeper than the average analytical human mind can grasp. But we can recognise glimmers of the truth when we see it, because it resonates with inner infutability. The closer we get to the truth, the more universal it becomes.

So, how do we recognise truth when we find it? The short answer is it is filled with life, even in death; without a second thought, it instinctively flings us to the floor, weeping, laughing, shouting for joy or punching the air in victory. Similarly, how do we recognise evil when we encounter it? To be blunt: it doesn’t give a single iota for you, not a dam for your soul, nor a single yot for your journey, for it is hell-bent on your destruction.

Same Story, Different Time

The same sunk faces amassed on the borders, in the reserves, the transit camps.

The same loss etched in expression across Tibet, Rwanda, Kosovo.

The same resonant legacy in the anguish of Auschwitz, Jericho, all along the Red Road.

The same ancient record played out, stuck in cyclical revenge.

The same trust blinded by Betrayal.

The same forgotten Humanity,

The same dammed inhumanity.

The same distorted belief that `all delusion is in the minds of others!

The same rant restated:

To rob a people of their power cut their hair,

To rob a people of their pride, burn their homes,

To rob a people of everything, take their land.

In a different guise at a different time, we all stood in the stench of smoke and shit and death.

Their loss is our loss, their present our personal past.

To heal is to look inward, as landlessness was in man long before man was landless.

To remember standing, sometimes in bare vulnerability, sometimes in spitting indignation.

To feel the grief, begin crying, and never stop.

To sob and scream into the soil, until our heart recalls the common call.

The call of humility.

A humility that rises up and says enough! NO MORE!

Humility with boundless capacity to rebuild, re-grow and in time, reconcile.

Then we will know.

When the bomber looks into the eyes of the burnt and says "my brother,"

and the answer is "yes, my friend."

(The Cabin, Overdene, Northumberland, 1999)

Jerusalem (27/12/1993)

The friendly atmosphere of Al-Arab hostel provided a packed and ramshackle place from which to explore Jerusalem. Early one morning, I climbed amongst students sleeping on the roof and looked out over minarets and domes. The call to prayer crackled out over the rooftops from multiple speakers. This was not a place where the spiritual was an afterthought. Religion was the currency, the electricity, the guiding force of each and every day, for as long as can be remembered.

I walked the streets and walls of old Jerusalem, stopping to talk to a Palestinian law student working in a pizza place. He told me he thought of himself as an exile in his homeland, and it was down to us, the Brits. He said he had freedom of speech in Israel, and he would not necessarily be welcome in Arab countries. This was not a battle about radical religious beliefs, simply one of land, he said. Palestinians, he told me, are highly educated, travel the world to study at different universities and make excellent businessmen. (Just like the Jews, I thought, not for the first time and not for the last).

Refugee Camp Amari. Ramallah, West Bank (30/12/93)

Occupants are not permitted to move in or out without permission. Ali, the manager of Al-Arab Hostel, suggested he was ready to die to obtain freedom in the country where he was born. He showed us remains of destroyed houses, evidence of the bulldozer work of Israeli troops. He talked of the detention of children as young as 12, and all around, the poverty of his people, and unease about access to education. Wire and fences, and gates had been removed following recent agreements, a loosening of overt regulations, although he maintains that the same regulations are still operated covertly. Ali sees no hope for change. Children followed us everywhere with smiling faces. I gave them my camera and they went wild with it. They also took great pleasure in holding my hand and doing karate chops. On leaving, we went through a checkpoint where an Israeli soldier pointed a gun at us, ready to shoot if necessary. The Palestinians seem to live under the same persecution as the Jews once did.

Ali suggested that Palestinians were being used as scapegoats to maintain stability between native and non-native factions in Israel. Between Russians, South Africans and Jews. In fighting one enemy (The Palestinians), groups with different views of the same cause come together. In the case of the PLO and Hamas, the power of their unity is weakened when the opposition gives in, just a little. When there is no longer an enemy, the groups become divided once more. The camp was formed after the 1948 formation of the state of Israel by Britain. After the event, Palestinians were subject to attacks and therefore grouped together in defence. At this time, they moved to Gaza and the West Bank (which was then Jordan). Here they lived in UN tents. The Six-Day War produced the annexation of the West Bank, and they were once again stranded. They then started to build more permanent structures.

A young soldier points his gun at the minibus window. Our driver searches for his identity card. Failure to produce papers results in instant detention. A fellow soldier inspects the underside of our vehicle. Nothing is left to chance; there is a tense silence amongst my travel companions.

Ali, owner of EL-Arab hostel, is taking us to his home, the UN refugee camp Amari, near Ramallah in the West Bank. He gives simple “yes” and “no” answers to his inquisitor; the distrust between them is mutual. Ali, now around 35 years of age, has been in and out of prison since he was thirteen. His first imprisonment was for terrorism, or more precisely, stone throwing. The young man with the gun standing before him has the looks of a seventeen-year-old, a conscript to the Israeli army. I wonder if he understands the implications of his job. The previous day, I had seen a group of soldiers standing outside a house in the Arab quarter. I asked them what they were guarding, and they said they didn't know and didn't ask why. The whole place is incongruous.

As we leave the checkpoint, I look up to my right and notice a large gun tower; there had been more than one firearm pointing in our direction. Today, little traffic is allowed through the barrier for fear of terrorism. The effect is the creation of an isolated Palestinian enclave with people dislocated from their families and sources of income. We drive through the checkpoint and the walls of the camp. The barbed wire fences, which were recently taken down due to the latest peace process, are now effectively replaced with an economic blockade. As we step out of the minibus, the children come running towards us from all directions, laughing and grabbing at our sleeves, they pull us through the streets.

The houses are made of concrete and corrugated iron and are packed tightly along narrow streets. We are led to what appears to be a pile of rubble. “The Israelis suspected the man who lived there was a terrorist, so one night they blew up his house,” explains Ali. This, you remember, is a UN-protected area. I’m staggered at the joy of the children in such squalor. I give them my camera and they excitedly take photos of each other, with what turn out to be excellent results. We are then taken to Ali's home. It consists of two rooms, one with a table and one with a sofa and some chairs. We drink sweet tea and listen to his views. He is taking a risk bringing us here. Few in the West know about Palestinian oppression; it does not make the news (Then). Ali, like most Palestinians I meet, is highly educated, although I feel some of his talk is propaganda, I begin to get a clearer picture of the conflict in Israel. In the end, it is the location of lines on a map drawn up by the British that is the most tangible source of disagreement. The formation of a Jewish state in Palestine could now be seen as a short-sighted act, but at the time, under pressure of a post-war refugee crisis, a ready solution. What becomes apparent, however, is the Israeli abuses of human rights. Detention without trial, restriction of movement, control over development, curfew, limited access to education, and other forms of subtle mistreatment are widespread. It is a quiet oppression. Many of Ali's friends have fled the country to obtain a better education, but few have managed to return. The only way Ali can gain equal rights in his homeland is to join the army which suppresses him, and become a citizen of Israel, he would rather die. Due to continuous frustrations, he is pessimistic about the future. For one thing, he believes America has an interest in perpetuating internal instability to promote international stability, giving America a foothold in the Middle East.

The extremists on both sides are so entrenched that sabotage of the peace process has become their mutual aim. The resentments run deep through generations on both sides. Parallels with Northern Ireland are strongly evident. Times change, yet some, fuelled by religion, blindly refuse to compromise their positions. As I am later reminded by an Israeli friend, “between two extremes lies the golden way.” Those who stand on the middle ground continue to move tentatively forward.

The Palestinian dream is a return to a self-ruled land, a dream that is unnervingly similar to that of Jewish refugees throughout the millennia. Surely, then, these two peoples have much in common with which to rebuild trust.

Egypt

Humbled in Huragada (1993)

There’s not a single cash machine in Cairo. So, I take my chances boarding the night train to Luxor with only 100 ED on me; this is exactly enough to get back to the Taba border with Israel, with no stopping and no fun. Onboard, I strike up a conversation with an Egyptian-American, who offers me 50ED and his address if more is needed, yet he only knew me for half an hour. When I get off the train in Luxor, I repeatedly tell the hustlers I have no money, but one guy says I can stay at his hostel for free. I say yeah? And shrug him off. He chases me and I keep walking, but he catches up with me. I ask him again what the catch is, how can he do this? “Because Egyptian hospitality is not like English,” he replies.

Gulp. I’m eating humble pie, but I still ask the other hustlers if I can trust him. They all say yes. He buys me tea and a sandwich and takes me to the hostel on his motorbike. I’m so grateful, I decided right then and there to assist him by convincing another Englishman to stay at his hostel. When we arrive, I dump my bag behind and go and help him catch people coming off the next train. He can’t believe it, (neither can I!) “This is the first time I have ever seen an Englishman doing this!”

To pass the time, I rent a bike and ride into the agricultural land around Luxor. As I roll into the villages of the farm workers, everyone greets me with “good morning,” “salaam,” or “hello.” The children follow me, and I let them have a ride on my bike and a shot or two on my camera. They lead me into a field and give me some sugar cane to eat while they stack up the bike rack with even more. I take off, riding through the village following the Nile. Everywhere I go, the children follow me, and I stop to play football for a while. Down by the river, women were washing clothes in the Nile as they have done for millennia. By now, I’m feeling humble and sad about my Western ways. The kids ask for money, but I have none to give. The “elders” of the village, including the women cloaked in black, are friendly in their greetings. A young boy invites me into his front yard to meet with his family. Healthy little lambs walk about freely; goats and a bull are tied up outside. Sugar cane covers the floor.

I enter the house. It consists of two rooms; in the far room, the women are making dough for bread; in the room I’m sitting in, I’m unaware of a young lad sleeping. There’s a TV and radio, and the atmosphere is warm despite not being able to communicate too well. The women smile and give me bread and a warm drink made from fresh goat’s milk. The mother of the house imitates milking a cow. The young lad tells me he sleeps all day because there are no tourists. We talk about tourists, England, and music. I take their address, thank them and leave humbled. They gave so freely and expected nothing in return.

As I cycle back to the hostel, a young boy stops to show me how to use a water pulley. He asks for money. I quietly ask him how he can expect me to give him money when I have none. He eventually stops asking and shakes my hand. He tells me how tourists use young boys as prostitutes [was he telling me about himself?]. Later, I talk to a felucca captain who shows me photos of his tourist friends. The guy at the hostel asks me to stay and work for him. I explain how I think it’s best to leave, thank him and catch the long, hot, dirty bus to Huragada, humbled.

“Round here, the land is too close to the sky,

Shadows stretch to the sea from the corner of a barmaid’s eye.

Whistle tunes linger from ripened womb,

around the smoke of this barroom.

Reflecting Mother Mary's guilty gaze,

and the lilting turn of phrase.”

Ireland

A Little Lyrical Light (1993)

The yearning for Ireland came from an urge to go west, towards the Atlantic, where the sun drops into the sea with an Alka Seltzer fizz. I took a flight with long views along the snaking Tyne Valley, crossing to the Pennines, the Lake District and the Irish Sea to Belfast, where British Soldiers were still patrolling the streets in personnel carriers.

As ever, I was seeking out the songs and the writers. The Irish have a musical gift for witty wordplay; their poetry is thought to gain extra crackle in the magical act of translating Gaelic to English. I was reading James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and the mind-boggling ins and outs of Irish history while listening to Van Morrison, the Pogues, Bob Geldof, Matt Molly, Liam O’Flynn, The Chieftains, the Dubliners and so on and on. Following the muse, I headed down to Dublin to visit a friend’s family and joyfully hit the music scene. All I recall was the unfailingly friendly hospitality, the lilt of fiddle tunes and endless craic.

Back then, the pace of life was significantly slower, the roads were still small country lanes. Ireland was emerging from the backwaters into the modern economic powerhouse it is today. I’m grateful I got to see it with a touch of the Rare Old Times. As I pushed on towards County Kerry and Dingle, I recorded scenes from my journey, in A walk along the Kerry Coast, (Inspired by Bob Dylan’s A-Hard Rains-A-Gonna-Fall).

A walk along the Kerry Coast

(Bog View Hostel, Inch, 1994.)

So, what did you see my blue-eyed son?

I saw rainbows stretched over moorland, sunshine, white in the sea;

I saw sandbars in the distance, white cottages, contrasting green; wave after wave after wave (rave on, rave on).

I saw rainbows over sand dunes, over bog and salt marsh; hail, rain, sun and cloud.

I saw a robin on a wire and lichen on rocks, 10,000 years old.

I saw torrential mountain streams and heard the ever-present rumble of water moving rock.

I saw an old lady shuffling down the road, Aryan mist hanging off her shoulders.

I saw the sun's faltering glimmers of golden light; green moss, hair grass, streams meeting the sea and the ever-present Atlantic.

I drank a Guinness by the fire in an orange pub, with vegetable soup & apple pie.

I heard commonplace talk about the weather:

"Round here the land is too close to the sky, shadows stretch to the sea from the corner of an Irishman's eye..."

I walked a dark road to the light of an old school house, and the stilling sound of the sea, the sheep, the stream.

I sat by an open fire, a baby and a mother, the father and a friend fresh from Dublin.

And sank to bed satisfied, with a book and a beer.

Northumberland Song

(To the tune of Rawhide)

I ride upon the black steed; I’m coming home to you.

I ride upon the white steed; I follow the curlew.

The spirits of our ancestors rode on winds upon these lands,

Brazen through bracken bush and Dunstanburgh sands.

(Chorus)

Northumberland, I’m coming home to you.

Northumberland, I follow the Curlew.

Northumberland, I’m coming home to you.

Northumberland, I follow the Curlew…

I follow the Curlew.

(Verse)

With Reiver passion in our blood,

Steel bonnets upon our heads.

We cut swathes upon dales for our children to run ahead,

Now the mists have risen up from the valley floor,

The thousands slaughtered on this land don’t haunt us any more.

(Chorus)

When our grandfathers were called up to fight in foreign wars,

There they built geet concrete blocks there, along our shores.

To protect their families, they did what they had to,

Though it hardened their hearts, your love it saw them through.

(Chorus)

The ruined cloistered abbeys held Jesus’ love in stone,

Their roofs have fallen in, and now the message lifts once more.

It’s written up in sacred script, up in Lindisfarne,

Love your neighbour as yourself, do no man any harm.

(The Cabin, Overdene, Northumberland 2000)

England And Scotland

Islands, Castles and Gardens (1994-2011)

For seventeen years, between 1994 and 2011, I was based in the UK, taking occasional trips abroad, but not writing too much about my travels. While studying Landscape Architecture, I spent three months on an Erasmus programme in the newly post communist Slovakia. I travelled to witness a solar eclipse in Romania, visited Auschwitz in Poland, spent a night under the stars on an Australian sheep farm, motorcycled through Norway, took the calmest North Sea ferry from Amsterdam to Newcastle as there has ever been, and became seriously ill in an idyllic South East Asian beach hut. But I wrote not a word.

I flirted with Buddhism and yoga, was tempted by the monastic life, but never became a devoted monk, despite a yearning for faraway places, organic gardening, community, contemplation, fasting and the spiritual life. I spent hours locked in unproductive meditation and briefly stayed at a community connected to Samye-Ling Monastery in Dumfriesshire, and their retreat centre on Holy Island, off the Isle of Arran. Intrigued and content, but lacking trust in provision, I eventually gave in to the nagging idea that I should be making money with my qualifications. I departed Scotland to go to the big city, attempting to make a living as a landscape gardener in London. Returning to Newcastle the following year with my lonesome tail between my legs, but following my heart, I began to find a group of friends in Northumberland who took on a similar spiritual approach to life. Though somewhat sedentary, some of the places I ended up working during these years provided intriguing insights into the world, such as polishing silver as a Butler for the Duke and Duchess of Northumberland.

During the shooting seasons of 1996-99, I worked as a Butler at Burncastle Lodge in the Scottish Borders and the Castle of the Duke and Duchess of Northumberland at Alnwick. We would serve family, friends and dignitaries at the castle, whereas our guests at the shooting lodge were invariably American ‘Guns’. As far as I went the extra mile to serve them, the Americans reciprocated with warmth and generosity. “This is a fine place you’ve got here, Marc,” said one, as I carried his suitcases through the front door of the lodge. A small statement, you might think, but it typifies the American attitude – an Englishman would rarely compliment the Butler on the surroundings.

My mentor, Household Controller, Mr. Patrick Garner, was a gentleman down to the “T” too.

Trained at Buckingham Palace, he never betrayed a confidence and always held the door open for me and others. So, it was no surprise that Patrick opened the door to my job in the borders.

Did I want to run a shooting lodge in the Scottish Borders, he asked?

Daunted, I said “Yes!”

Once inside the Lodge, our American guests would make themselves at home by the fire, accompanied by the lilting Scottish fiddle of Martin Hayes. The ticker-tape patter of stocks and shares prices on TV would compete with the 4 pm lit of Scottish Fiddle, Camomile tea, Lapsang Souchong, cucumber sandwiches, crumbly shortbread and a steaming china tea pot of Lady Grey. Many were high-flying CEOs for banks, Ford, Monsanto, Law companies, and the drug industries. Not one of them had corporate horns or fangs (as some of my activist friends thought). All were courteous and kind, with, as you will see, with the odd forgivable slip. One particular shooting party would come back each year, and we built a great rapport.

One Halloween, they switched the lights out and hid under the table to scare the staff… in their pyjamas. (Let me repeat - CEO’s hiding under the table in their pyjamas!) We returned the prank by putting costumes on the stuffed animals (forgive me, Your Grace, if you’re reading, but I know you have a wicked sense of humour too). For one memorable golden wedding anniversary, we hired a Scottish Piper and drove to Edinburgh for Cuban cigars to go with the Single Malt Scotch. It was a hoot. An American gentleman is generally never more content than with cigars and Scotch.

The job taught me an 'awful' lot about the fine things in life, like full-bodied clarets, smokey-oakey-aged whiskies, pungent cheeses, kedgeree, venison, quail and courtesy. One morning, I came downstairs and was greeted by an extremely well-mannered Southern Belle in the kitchen: “Marc, can you tell me who was sleeping on top of me last night?” I raised an eyebrow, and we both burst into laughter. (She meant who was sleeping in the room above!) Stories like this stick, like the two billionaires discussing the seating arrangements on their private jets: “How do you prefer your seats, Bob, theatre style or down the sides?” They would do that corporate thing of having Jack call John to speak to Jill’s people about Joshua. The tips were great too. One day, I had seven hundred dollars slapped in my hands for three days of work: “Thank you, Marc, everyone has chipped in…except him,” said the main man, pointing at a red-faced guest. “You son of a bitch!” he retorted. I quickly exited the dining room and left them to it.

The English guests were warm and funny too, but there was something stopping me from being myself the way I could with Americans – my impostor syndrome based on coming from different worlds and classes. Despite this, both the Americans and Brits taught me a vital life-long lesson: never judge a person by their wealth, or indeed lack of it, we’re all human after all.

I still dream about my Butler days, but I couldn’t see myself marrying the job the way my boss did. Patrick died in Syon House, London, sorting out a cupboard. He lived for service, died for service, and wouldn’t have it any other way. In heart heartfelt tribute to him, the Duchess said he was one of the family. It was the same with the American guests. Some of them wanted to take me home. When the taxi tyres crunched up the gravel to take them to the airport, we hugged and waved them off, as family.

***

All the while, some latent talent was struggling to express itself. With wages from my service for the Duke and Duchess, I bought a cabin in the countryside and started designing and developing gardens in Northumberland. A fountain of poetry started flowing as I settled into my new home…

The Field

There is a field, a green green field,

Where the hearts of humankind are still.

Were peace flags wave on winds that for so long called out your name.

Where your brothers and sisters await, in recognition their hearts bursting open.

To hear the field is to listen to the call of your heart.

To see the field is to look into eyes of souls who have never been apart…

To speak poems of the field is to remind all of our destiny which awaits.

To feel the field is to drop to your knees, weeping for all the times you thought you were not loved!

You are loved, always have been, always will be.

When you find

The Field.

West Road Café, Summer 2000

***

The Tribes are Returning

(Alternating guitar chords: e and a minor to a Native American drum beat)

The tribes are returning,

Tribes are returning,

Lifting us all higher, lifting us all higher!

The tribes are returning,

Tribes are returning,

Lifting us all higher and higher and higher,

The tribes are returning.

The tribes are returning,

The tribes are returning,

Lifting us all higher and higher and higher, the tribes are retuning.

We are all one tribe,

We are all one tribe,

One tribe,

One world,

One voice,

One Song,

The tribes are retuning…

As the new millennium turned in 2000, I sold my cabin in the country and moved into a community townhouse in Newcastle. There were four residents, leading largely separate professional lives, yet pulled together by the genial backbone of the community: a food sharing payment system that for generations of residents withstood the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune. I passed the cook-us-a-meal-test and moved in, making us five, a household complete: Jan, Ian, Olga, Kate, Marc.

The curtain-free living room was jammed with a sofa and a TV, but no one gathered to hang out and talk, other than occasional meal times. The hallway was carpeted purple, and the understairs cupboard was jammed with possessions previous tenants had left behind. We set to work. Out went the carpet, and in came a floor sander – cleansing and beautifying the downstairs floors. Junk was chucked out and the cupboard under the stairs became a computer room, come pantry. Bikes no longer blocked the hallway but were hung from hooks. The TV exited left. With typical relish, one of my flatmates broke open the once-sealed fireplace, cleaned the chimney, surrounded the hearth with teak - reclaimed from university laboratory benches - and installed a fireplace. The kitchen was teaked out too, the yard was cleared, and the garage slowly became a workshop. The beating heart of a home was returning: a heart crowned with a piano purchased with what little money I had and delivered from a friendly neighbour’s house with four friends squeezed into in a white van. Fire and music lit up the living room. Long play records appeared on the shelves. Curtains appeared at the windows. Suddenly, the house was filled with people popping round for pints of tea or a beer. Day and night, night and day, “Harry worked on the railway,” played on the stereo, Bach cello concertos and Woody Guthrie echoed down the hallway. The parties became longer, legendary, all-night affairs. Hearts were won, lost and broken, like the trunk of a wounded cherry tree outside, severed by a thief attempting to steal my motorbike.

But, there was a thief in the house of love.

The inspiration that inspired my poetic writings halted abruptly when, unwisely, I took a cascading series of wrong turns and let go of the handlebars. Within just a hair’s breadth of applying correct thinking to a series of decisions one way or the other, I committed myself to a regressive road, and kept committing, pressurising myself to commit. Impatiently mistaking a long-held vision of the future as one surfacing in the present, and confusing healthy letting go for abandonment of self, my metaphorical motorbike ground to a halt in quicksand. Road signs were all around, but I chose to suffer a loss of good guidance that would take many years to recover. An ocean of anxiety overwhelmed me. Waves of nausea nagged away at me over a full ten-year period. From sailing in a fair wind, I sank waist deep in the big muddy. I continued trimming tomatoes with unemployed miners, selling organic vegetables at a farmers’ market, and growing apricots for aristocratic ladies, but something had been broken. I tried every possible therapy to fix myself, but nothing worked. Close relationships collapsed under the strain, my internal compass was spinning this way and that, until a good friend arranged a trip to Greece…

In moments of losing everything, we find everything.

Greece

Debt, Heartache and Joy (2011)

It was 30 in the shade and too warm to work, especially for an Anglo-Saxon in Greece. My compatriots and me were touring coves of the Chalkidiki in Northern Greece; winding our way amongst three long fingers of land stretching out into the aqua marine Aegean. We were fresh from two days of swimming, sun and relaxation at the University of Aristotle beach campsite. Now! Imagine that I thought...a beach campsite, subsidised by a university! I was sitting under a tree sipping tsipouro, chatting with Stelios Tzirgas, an electrical engineer from Athens, when the conversation quickly turned to the debt crisis. He talked of a standstill in his industry, the futility of rioting, and how he hadn’t been paid for six months. Amongst all his talk, one phrase resonated resoundingly: “I work very hard,” he asserted.

Though I was completely unaware, the journalistic urge that had been sparked some twenty years earlier, in Israel, was slowly being reignited. That simple phrase, “I work very hard,” triggered a story I would later write about a political schism in the Greek psyche. My Greek friend joked, “In the private sector, they work for eight hours and get paid for four, in the public sector, it’s the other way around.” Arriving at 4 AM in the Northern capital Thessaloniki, I took a walk through the market as it woke for another working day. The experience did not leave me with a sense of Greeks as workshy skivers. Like any other street market around the world, the people had hard work etched in their expressions.

As time passed, I began to hear stories of ambiguous benefits, bogus bonuses and inflated wages in the public sector. Of teachers who turn up for morning lessons, then go home for the rest of the day, and of policemen taking bribes. Every day tax evasion seemed common practice whilst offshore evasion amongst the elite siphoned billions away from government coffers. Greece, I was informed, had an estimated black-market economy of 30%. The public and private sectors took full advantage of the pension system too; early retirement at 50 or 55 was possible for jobs classified as “arduous,” such as hairdressers, radio announcers, waiters, musicians...

At the heart of the crisis, there was an internal dilemma. To reform, Greece was required to embrace neoliberalism and privatise or sell key assets [Which they duly did]. But the Greeks were aware of a certain malevolence; that the lure, like the mythological Scorpios, had a sting in its tail. Meanwhile, people sitting in the sandy coves of Chalkidiki showed no outward signs of suffering. They swallowed seafood, supped beer, sang, swam and smoked cigarettes. The world was still spinning, and the sun still rose behind Mount Athos in the morning.

That was the first time I saw the mountain. From the other shore. We would depart soon, but the urge to return and climb Mount Athos had been planted within.

A romantic love affair had failed, for good, and any remains of denial evaporated into the clouds. Sobbing as the wheels of the aircraft left the ground, I could hold the tears back no longer. I let go. Greece, the land of the goddess, receded below as the pilot set course for the grey skies of North East England. A kind woman next to me handed me a paper handkerchief and said: "I think your friend is crying too." I looked back to see my travel companion across the aisle: head back, eyes closed, and mouth open, snoring. I spluttered laughter amongst tears into my tissue...

United Kingdom

Balls of Steel (2011)

Boom! A deep thudding explosion vibrates through the air. "Contact right!” goes up the cry. A group of trainee journalists in transit with me all move towards the right-hand doors of the Land Rover. I’m sitting in the passenger seat as navigator. Out of the corner of my eye, I see a man in a balaclava with a pistol lunging for the door. I push at the driver and shout: “Out your side,” but he doesn’t budge...fuck. The gunman swings the door open and pushes the pistol towards me, shouting: “Get out of the fuckin’ vehicle.” I grab the gun and twist it away from me towards him. He forces it back, and I twist it again. He drags me out of the vehicle and puts the gun to my head.

My compatriots are fleeing downhill. “If you don’t come back, I’m going to kill him,” shouts the abductor.

"One…"

They keep running…

"Did you hear what I said?"

"Two…"

They keep running...

(The realization dawns: fuck they’re are not going to come back).

"Three...get down on the ground and eat the fuckin’ dirt.” “Who are you and what are you doing here?” I keep schtum. ‘Fuck you’ I’m thinking inside. Despite having been abandoned, I’m not going to say anything that will compromise my colleagues. On some level, I’m aware my resistance is giving them time. I’m not going to tell him anything.

He pins me against the Land rover and has a go with the old verbal, calling me all the jack- ass names under the sun. I go mute… and calm inside, there is no way I’m going to speak. The abuse just seems to bounce off. He picks me up at screams at me eyeball to eyeball.

“If you don’t fuckin’ talk there is a group of men down there that are going to bend you over and fuck you up the arse till you can't take any more, do you hear me? Do you understand?”

“Yes”

What’s your name?

“Billy Wigham” (the man who ran a chip shop in my village when I was a kid).

What are you doing here? “I’m on holiday!”

“You’re not on fuckin’ holiday, you liar.”

“What are the others doing here?”

“I have no idea, I’m not party to that information.”

"Not party? What kind of poncey language is that bullshit?"

I remain silent.

Silence, it seems, is my natural reaction; this is me…

***

Later, the military man turned actor hands me back a button from my blue shirt.

“You must have balls of steel, no one has ever attempted to wrestle the gun out of my hands before!” he says at the debrief.

He shows me the cuts on his hand from the pistol wrestling.

“You know, I was under control. I’m trained to do this, and that was the hardest treatment I have ever given a student. You did so well, Geordie mate, alright."

He gives me a handshake and a pat on the back.

“You might have bad dreams about this tonight...”

I wake in the morning dreaming about a cat that has bowl problems…there doesn’t seem to be a connection, but who knows? Maybe the subconscious has a way of excreting stuff it no longer needs.

On the train home the next day, I understand a little of why soldiers and foreign correspondents go back into the action time and time again. After three days of running through the woods, navigating in the dark, spotting mines, treating wounds and learning short-hand radio, civvy street seems dull. Deathly dull…now there in lies a contradictory conundrum. I was squatting down in temporary accommodation to keep mobile, save money and avoid signing a binding contract, when a friend sent me athe link to an advert:

Media Volunteer Wanted. CPAU, Kabul, Afghanistan.

Environment Training Notes

How to avoid being taken hostage:

“Assess kidnaps, criminal and political activity. Beware of volatile areas. Leave a trace. Keep in mind four pieces of information only you know, e.g. first car, pet. Prepare duress statements – things you can say that are not true to indicate that you are under duress, e.g., I miss my dog (when I don’t have a dog). Hotels: Book two rooms. Beware of people checking baggage. Be quick, confident. Change rooms during a long stay. Floors three and above are better. Lock the door, wedge it. Do not answer. Use a spy hole and door chain. Be wary of and secure windows. When leaving the room, do not hand the key to reception.”

Afghanistan

Searching for the Lion (2013)

Ever since watching videos of Ahmed Shah Massoud flying a helicopter up a precipitous river valley in the mountains of northern Afghanistan, it had been a dream to go there, to the only place left untaken by the Soviets or the Taliban, to visit the tomb of the legendary ‘Lion of Panjshir.’ Massoud’s portrait hangs all over northern Afghanistan, in cafes, shops, police cars and in taxi windscreens. He oozes handsome charisma, like Bob Marley, but with a bazooka. His reputation as a strategist and fighter secured his place in history long before two Al Qaeda-linked suicide bombers masquerading as journalists detonated their deadly devices in his presence two days before 9/11. His death was no accident of timing -he was a major thorn in the side of both the Taliban and Al Qaeda. Al Qaeda, incidentally, means “The base,” a reference coined by a commander who served under Massoud before switching allegiances. “The base,” at that point in history, was Panjshir.

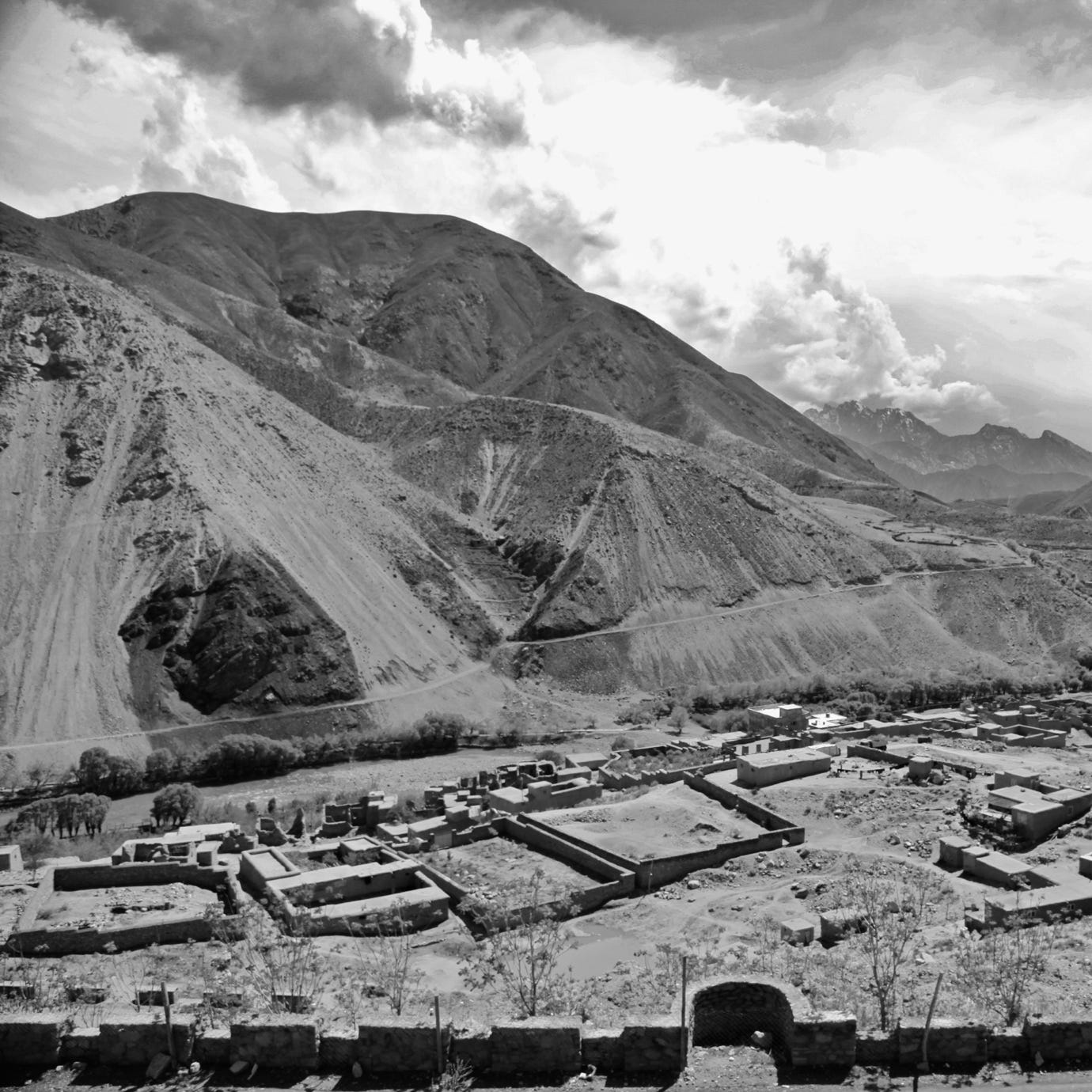

The Panjshir valley is a geographic safe haven running through the Hindu Kush from Afghanistan to Tajikistan. Accessible to the adventurous by a private company car -with a security guard included for a few hundred dollars, it is statistically known to be one of the two safest areas in Afghanistan, the other being Bamiyan, where the famous Buddhas were blown up. I judged it risk-free enough to find a cheaper route, but was frustrated by the empty promises of others to get me there; so much so, I even walked to a Kabul bus company office to ask the price for a fare. Weighing me up as a westerner, I watched their faces round the price up to $500; I left laughing, for a local, it would be more like $15. In the end, I got on the phone and called a friend. I promised petrol and food, and in return, I got wheels and good company.

The road north took us past Bagram air base, along a vast flat river-cut plain from which the mountains of the Hindu Kush rise impossibly sharp and steep in the distance. The occasional jet screamed overhead, sending rolls of thunder across the valley and echoing off the mountainsides. We passed nomadic herdsmen, possibly Kuchi, camping amongst their sheep in the foothills. Samsoor ran the car at speed through villages and ‘round curves, overtaking lorries with the typical hair-raising risks of youth -Afghanistan is not a place where ordinary road rules are observed. After climbing for some distance, the road began to run perilously close to the river Panjshir, cut inside a ravine of rock strata faulted at absurdly acute angles. We stopped at an armed guard post where my passport was checked – underlining the impression that the valley represented a kingdom of its own. A huge picture billboard of Massoud wearing a customary woollen pakul hat greeted us beyond. We continued crashing through high gorges, following the tumbling waters of the gorge upstream at a rate of knots. Mud-built villages clung to the hillsides while farms with grassy crops and fat-tailed sheep lined the valley floor. The air was as clean as the Pennine hills or the Yorkshire Dales, and the stone walls in the fields reminded me of home. It was liberation from the stifling enclosure and pollution of Kabul. We stopped for food at a restaurant perched on the riverside where we were served a fine spread of freshly fried fish, rice and lamb curries washed down with chai.

Further down the road lay Bazarak, the provincial capital of Panjshir, where Massoud's tomb can be found. On the outskirts of the town, a football stadium of significant size was nearing completion. I wondered what justified a stadium in such a remote place, but concluded peaceful recreation was reason enough. We sped past, onwards to the Mausoleum.

The tomb itself is set inside the arches of a domed tower edifice of stone and glass, itself set high on a finger of land dwarfed by white scree strewn hills. A tourist centre, one day ready to welcome the masses, “god willing,” as they say in Afghanistan, was under construction next door. Near the edifice, two men were preparing to pray, “Odd, that,” I thought, “they’re not pointing in the direction of Mecca!” A white bearded caretaker came out, cajoling and pointing at them. The men laughed and turned their mats to the southwest. We entered the mausoleum. It was a simple regal space, a raised black marble tomb covered with glass panels inscribed with passages from the Koran. We stood on deep red Persian rugs, and my Muslim friends cupped their hands in prayer. Massoud himself would approve; he was devout in observing prayer, but was widely recognised for holding a moderate, liberal interpretation of Islam. Intrigued by the veneration he holds, I asked my companions for stories that would illuminate the legend. Once, I was told, his enemies had mined the mouth of the Panjshir valley, trapping his forces inside. His response, full of native wit, was to drive a flock of sheep through the minefield to create a pathway.

Outside tanks, the rusting remains of the Russian invasion scattered the valley like tombstones. Afghanistan is known as ‘The Graveyard of Empires,’ and, if there is one place on earth that signifies the military defeat of the Soviet state, I mused, perhaps it is this. My time in Afghanistan would be coming to an abrupt end soon, too, but as we drove back down the valley at breakneck speed, I was blissfully oblivious.

Long Night’s Journey into Day

(First published in Freedom at 4 AM)

It had turned dark as myself and three colleagues sat watching a dubbed monosyllabic Turkish thriller on TV. The cleavage and bare legs of female characters in the cast had been blurred out in the name of conservative censorship. It was a heavy show, brooding with violence and soaked in surly tension, with burly blokes grunting short lines and swinging guns. My colleagues and I weren't paying much notice, but having a good bitch about work instead.

A week and a half earlier, we had been moved into this spacious and affluent-looking three-storey house in a poor end of town where our sudden appearance stuck out like a silver spoon in a soup kitchen. For financial reasons, we’d moved here instead of safer neighbourhoods within the so-called ‘Ring of Steel’. The well had run dry at our previous guesthouse. Our NGO was lurching from one crisis to the next. Finances were as low as the water in the well. We hadn't been paid, and the bosses had just unceremoniously ejected twelve Afghan staff from the ranks. The poor end of town had beckoned and there was plenty to bitch about.

Emily sat up suddenly. “Did you hear something?” she asked. I hadn't, and thought it must just be something falling over, so I didn’t accompany Emily, Hamza and Edward when they left the room to inquire. The next thing I knew, my colleagues were backing into the room with their hands in the air…